This story originally published on Feb. 20, 2017

By Jon Cooper | The Good Word

A true pioneer doesn’t seek the spotlight. Inevitably, it finds him or her.

Harvey Webb, the first African-American to play basketball at Georgia Tech, is a true pioneer and even though he avoided the spotlight for the better part of 50 years, it’s finally found him.

He won’t take any self-congratulatory bows but recognizes the significance of his accomplishment and is willing to talk about it.

“I realize now more so than I did then, what the accomplishment was. Now I can see the merits of it because I can say `I did do something that no one else ever did,'” he said. “It’s interesting to see these guys that have come since, the guys that have had the opportunity because back in 1967 the time was limited. You didn’t go to an all-white school. It just wasn’t done.”

Although he loved basketball and was quite good at it, Webb, an Atlanta native, who attended Harper High School and actually grew up best friends with William Sheets, who’d break the color barrier at Oglethorpe University, initially didn’t even entertain thoughts of trying out for the freshman team, the only option open to first-year student-athletes at the time because freshmen were ineligible to play varsity under NCAA rules.

“I never considered it at all. I was trying to maintain my grades,” he said, with a laugh. “It was unique. Coming from an all-black, segregated school, we weren’t on par with the level of education that they had received. We were in classes, calculus, we were starting on things that I had never seen before. The only reason I played basketball here was we used to play over in the old students’ center. We’d play every day. One of the guys who played said, `Man, you need to try out for the team.’ I tried out and I made the team.”

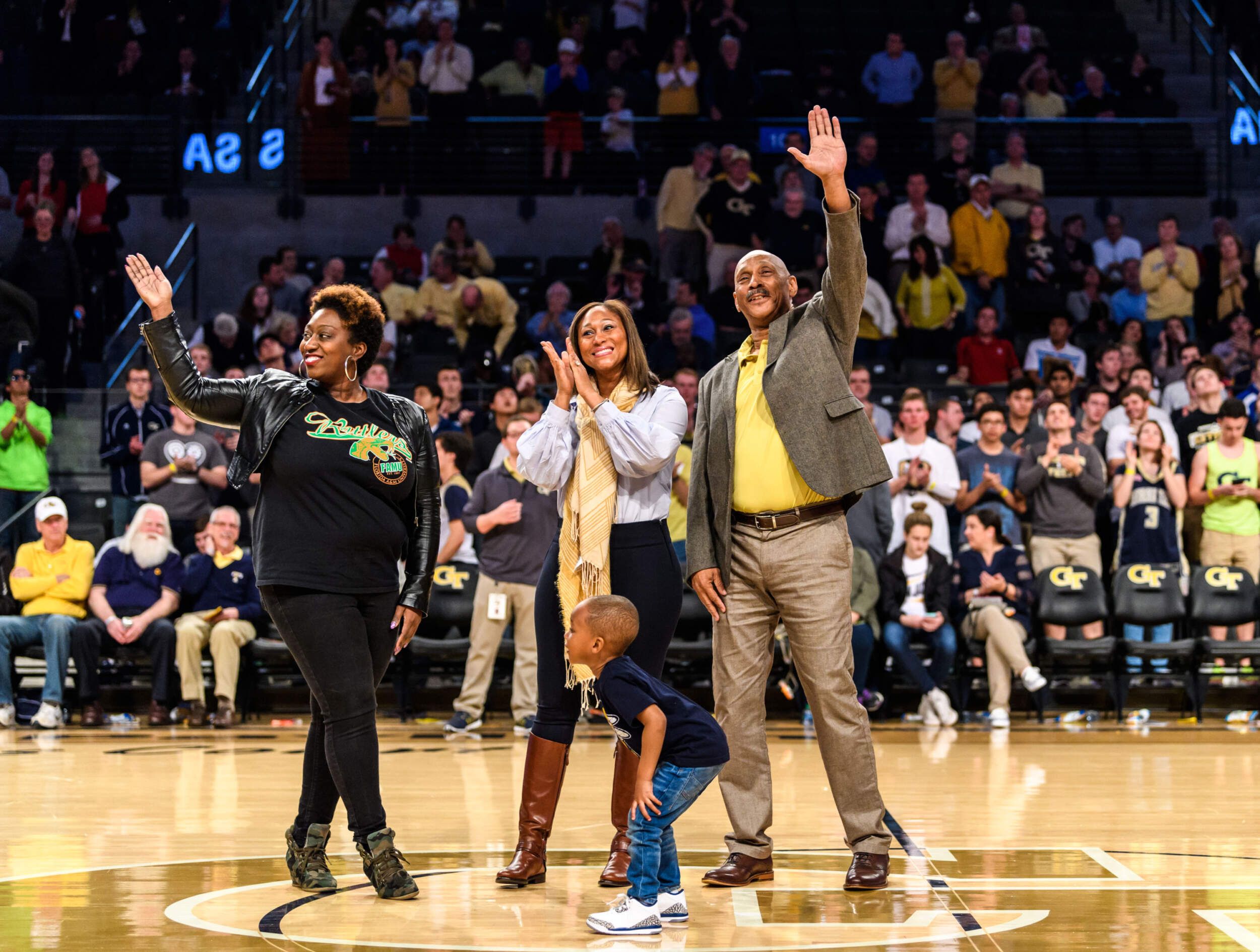

Webb (shaking hands with Tech director of athletics Todd Stansbury) and several other early African-American players were honored on February at halftime of Georgia Tech’s game with Miami.

From there, history was made, history that will be recognized on Tuesday night prior to Georgia Tech’s game against NC State, as part of the Institute’s celebration of Black History Month.

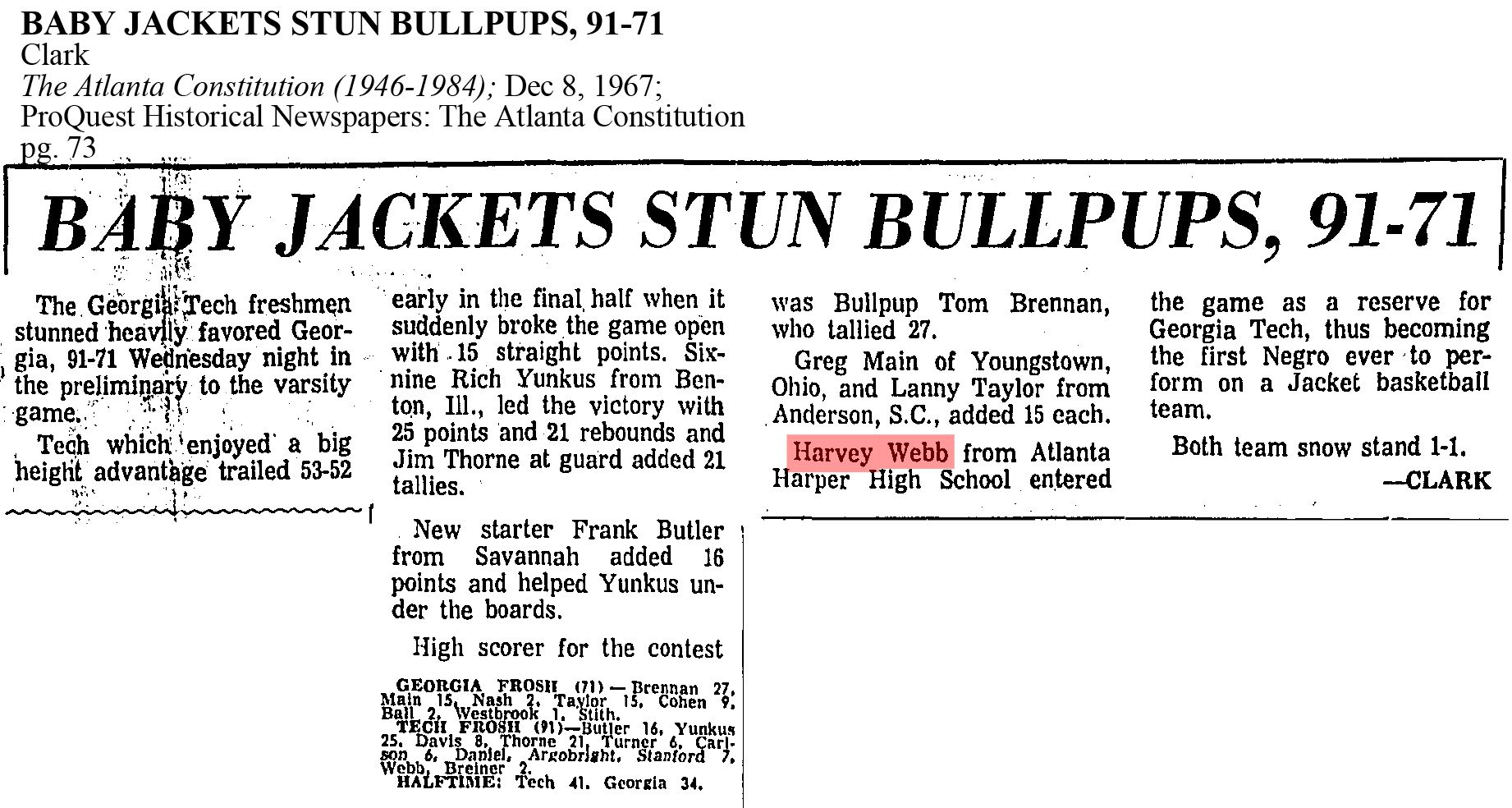

That Webb still reluctantly talks about making history isn’t surprising. He wasn’t ready to admit it at the time, when he took the floor for Georgia Tech for the first time against Georgia’s freshman team. Webb scored just two points in a 20-point Tech win, but his presence nonetheless earned him mention in the local newspaper the next day.

“[Assistant] Coach [Eddie] Jackel came up to me and said, `Webb, you’re making history.’ That’s when I got scared,” he recalled, with a laugh. “Before then I never thought about it.”

Two good things happened on Dec. 7, 1967. Harvey Webb broke the Tech basketball color barrier, and the Jacket freshmen beat Georgia.

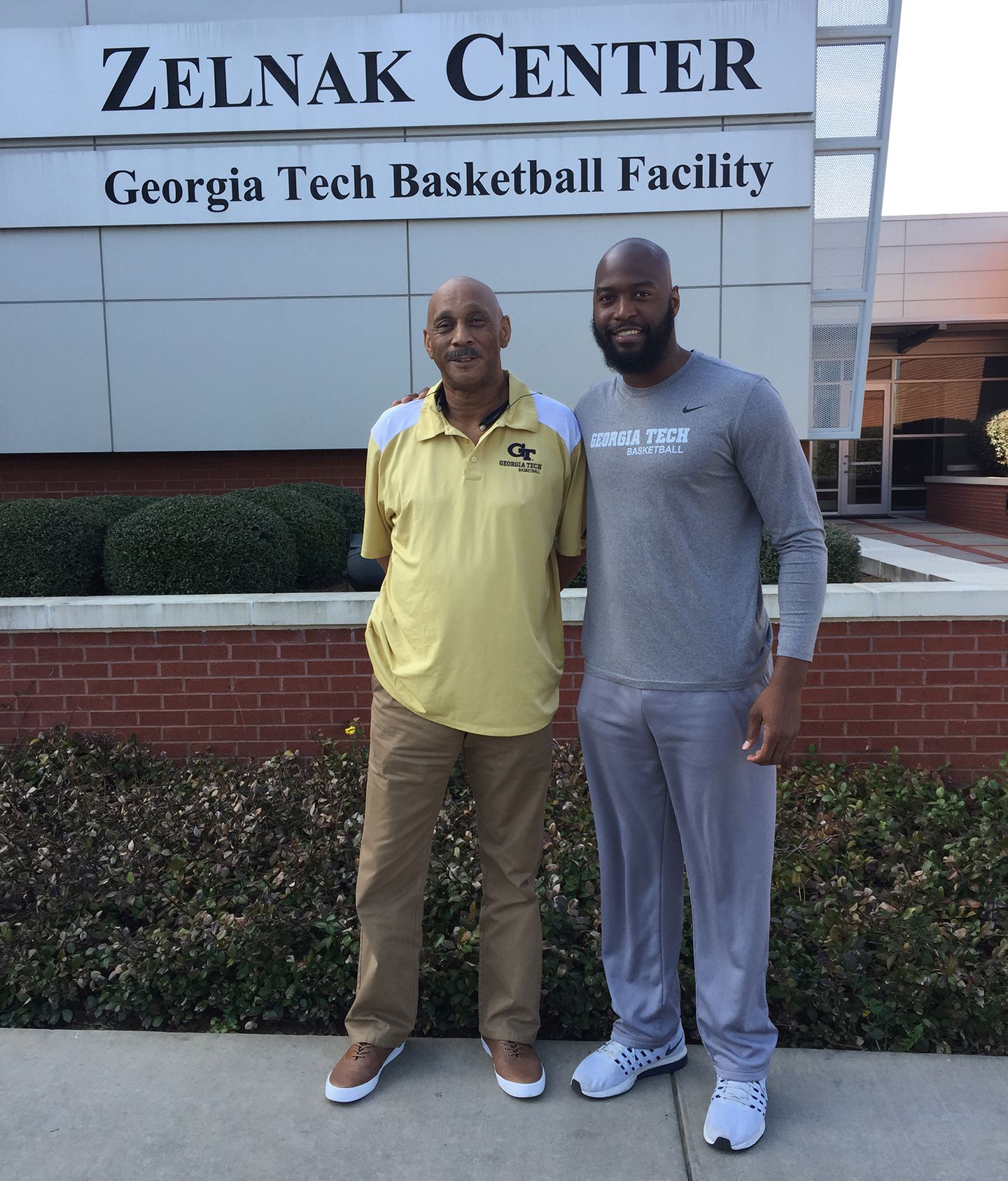

Former Yellow Jacket (2003-07) Mario West, now Tech’s director of player personnel, didn’t need a moment’s thought to realize the importance of Webb’s accomplishment. Once made aware of him through another Jackets alum and letterwinner, Tom Taylor, a local historian, West invited him to the annual Letterwinners’ Game on Jan. 27 at McCamish Pavilion.

“[Meeting Webb] was truly an honor and humbling experience because he was the first African-American to playing basketball at Georgia Tech,” said West. “He paved the way for other African-Americans, and to have the opportunity to pay homage to him and meet him was really cool.

“It’s very important to pay homage and respect to those that came before us and paved the way so we could further that history and legacy and pass it on to others,” West added. “Tom (Taylor) reached out and said I should reach out to Harvey because he hasn’t been a part of the program in years, and with his background he should be recognized and acknowledged. Once I found out about Harvey I acted right away and contacted him. Harvey has a great outlook on life, is very positive and has his experience as the first African-American basketball player.”

It was an experience Webb seemed more than happy to keep to himself. He admitted that if not for Taylor sending him a picture of the freshman team, many, including those in his immediate family might never have known about his accomplishment.

“I think my family is getting more of a kick out of it,” Webb said. “In fact, quite a few of my family didn’t know. It’s not something I talked about. Me and my sister, you mention it but that’s all. You never elaborated on it. You mention it for a minute and that’s the extent of it. It was just something I did as a teenager that I didn’t realize the effect of what I was doing.

“It took this to make me see. My daughter got on me because I kept saying, `I don’t really care.’ She said, `Daddy, YOU’RE GOING!'” he added. “My daughter, (Dr. Fonda Webb-Martin), when she puts her foot down, she puts her foot down. What got me was the pictures. Tom Taylor sent me the pictures of the team. I had never seen a picture of the team.”

Thanks to social media, specifically Facebook, and his niece (Sakari Balum, who teaches at Crim High School in Atlanta), who was especially eager to share, everyone saw the picture and began to shed light on his story.

“My daughter and my niece took the ball and ran with it,” he said. “Tom Taylor contacted me and said, `Harvey, you need to come because you were the first.’ Then it started dawning on me, 1967 was the year prior to Martin Luther King being assassinated and Bobby Kennedy, so it was a very tumultuous period. To go through that, I never grasped what I was doing, because it was just basketball. I loved playing basketball.”

There wasn’t any doubt he could do that. About the only problem the 6-3 Webb DID have was in being “a little hot-headed.” His temper led to him being banned from the gym at Harper for his senior year.

When it came to choosing a college, there was no mass recruitment or any video online. In fact, for Webb, basketball never entered the equation. He chose Georgia Tech for a different set of numbers, financial numbers.

“I was always a money man,” he said. “I always tell about the fact that if I go to Georgia Tech, it’s a whole lot cheaper than going to Morehouse. At Morehouse I had a four-year academic scholarship, but if I didn’t maintain my B average it would have cost more. So it just made sense to come here.”

While the late `60s was tumultuous everywhere, especially in the South, Webb found sanctuary in study at Georgia Tech. It had been six years since Ford Green, Ralph Long Jr. and Lawrence Williams became the first African-American students to enroll at the Institute and two years since Ronald Yancey became the first African-American to matriculate.

While he remembered being one of only roughly 13 African-Americans on campus, he recalled no incidents of race holding him back or standing in his way, on the court or in the classroom.

“The barrier had been broken, so it wasn’t as difficult,” Webb said. “There wasn’t any difficulty because you were here to learn. So anything else was irrelevant. You wanted to learn, and you wanted to better yourself. People ask me all the time, `What did I gain?’ I gained probably socially, socially in the sense that my ability to achieve was based just on me, that I could compete with anyone. That was the primary thing that I learned — that I could compete. I grew up in an environment where you didn’t experience white people. The white people I experienced were the policeman and the insurance man. That was the extent of it.”

Webb got to show he could compete on the court, where he stood out in a tryout he estimated had close to 100 players.

“I will say this. I was the best out there. There was no doubt about that,” he said, momentarily putting his modesty aside.

“I always talked trash,” he added, with a laugh. “That’s the nature of the game. I still do.”

He’d play on the freshman team with future Yellow Jackets varsity stars Rich Yunkus and Pete Thorne. The only color he remembered mattering was the white and gold of his uniform.

“It was more respectful than not,” he said. “One thing about being competitive, you’re going to have those that don’t like you anyway. But your game speaks for itself. You have to accept people for the skill level that they have.

“I recall being in Auburn, Ala., I remember a few catcalls and a few boos, stuff like that, but basically it wasn’t to the extent that it was so noticeable,” he added. “I didn’t give it a second thought, to tell you the truth. I knew about the issues that were going on as far as integration and so forth but I didn’t really put much stock into `Would I be accepted?’ It was just playing basketball. The guys on the team accepted me, I had no problems with them. It was fun.”

The fun would last only one season, as Webb suffered a chipped bone in his wrist against Georgia, when he was undercut on a layup, ending his season. Life would take over after that, as he left after his sophomore year.

“I was working and trying to go to school and going to Georgia Tech is not easy, especially when you’re trying to work,” he said. “I had just gotten married. I was working nights and going to school during the day. It was hard. It was extremely hard.”

He’d do just fine, however. He’d eventually attain his degree in economics from Georgia State and worked some 20 years in the banking industry, for Federal Reserve Bank, then at SunTrust for some 20 years. He’d eventually go out on his own with partners. These days, he does accounting work for people.

This newfound recognition, especially being invited back to the Letterwinners’ Game, meant a lot to Webb, who is actually coming to grips with owning the label of “Pioneer.”

“Because of the recognition that I’m receiving, yes, it means a lot more now because of what people have said,” he said. “I spoke to a lady the other day, she wants me to come speak at her church. I’m getting calls from people. I’ll be 68 this year, I’m beginning to see, `Maybe it WAS important. Maybe it meant more than I ever thought it did.'”

At the Letterwinners’ Game, he experienced the gratitude of those who have benefitted from his stepping up to play with the freshman team. That group wasn’t limited to Yellow Jackets basketball players and touched Webb, who still stays in the spirit of the true pioneer.

“Lucius Sanford did, everybody I’ve met has been so appreciative of what I did,” Webb said. “That goes hand-in-hand with the recognition, being appreciated, because now people are saying, `You did something wonderful.’ Okay, if you say so.”